An Interview with Asia Center Author Antje Richter

This week, we’re speaking with Antje Richter, Associate Professor of Chinese at the University of Colorado, Boulder, whose new book, Health and the Art of Living: Illness Narratives in Early Medieval Chinese Literature. This book offers reflections on health and illness in early medieval Chinese literature (ca. 200–ca. 600). Surveying a range of literary sources—essays, prefaces, correspondence, religious scriptures, and poetry—it explores the spectrum of views on health and illness expressed in these texts.

Could you give us an overview of your book?

In this book, I explore notions of health and illness in Chinese literary texts of the early medieval period. The book starts with an introduction that describes the rise of the health humanities in the last decades, explains terms and concepts such as health and illness, and concludes with an overview of the book’s main body, consisting of three parts.

Part I, titled “Between Self-Care and Self-Harm,” is a translation and discussion of Liu Xie’s “Nurturing the Vital Breath,” a chapter in The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons. I read Liu’s essay both as part of the tradition of writing about “Nurturing Life” and in terms of occupational health, as Liu depicts writing as an activity that requires considerable energy and, if approached in the wrong way, may cost writers their literary creativity, good health, or even life. Liu addresses the specific challenges that early medieval writer-officials faced, and he has a particular ideal of refined literature in mind, but many of his warnings and recommendations for healthy writing are still relevant today.

Part II, “Writing the Sick Self,” is dedicated to autobiographical accounts of health and illness, focusing on authorial prefaces in chapter 1 and on correspondence in chapter 2. I show how varied writing about one’s own health can be, depending on genre and on the role that health narratives play within a text. This is true among the five prefaces I discuss and even more obvious among different types of written communication, ranging from intimate letters to official memorials. The writers of these prefaces and letters pursue very different rhetorical goals when they bring their physical state into the argument, whether they are legitimizing authorship, maintaining close relationships with close friends and family members, or pleading illness to avoid office.

Part III, titled “Teaching from the Sickbed,” turns to sickbed visits as a prominent social aspect of ill health and a recurrent topic in early and early medieval Chinese literature. In chapter 3, I first analyze notions of health and illness in the Vimalakīrti Sutra. This Buddhist scripture takes a sickbed visit as its main setting and offers astute observations about the human body’s propensity for illness and decline. Chapter 4 turns to the emergence of poetry written while lying sick. That writing about one’s health became a more established topic in poetry, may have been due to the popularity of the Vimalakīrti Sutra among early medieval Chinese writers, especially the early fifth-century poet Xie Lingyun.A brief afterword brings the book to a close.

What drew you to this area of research?

I first noticed health reports and wishes for good health in early medieval letters, one of my main research interests. Starting from the earliest Chinese letters we know, these elements were clearly part of the epistolary formula. There are also letters, however, in which writing about one’s own health or the health of others is more than just a nod to letter writing conventions. Especially in the notes by the great fourth-century calligrapher Wang Xizhi, I saw a wide range of illnesses and treatments emerge as a subject of communication. What fascinated me just as much was Wang’s versatility and elegance in writing about his own maladies and those of his correspondents, and the ways in which his illness narratives contributed to the power and authenticity of his letters.

What was the question (or questions) that were driving the writing of this book?

Coming from Chinese epistolary culture and especially from reading intimate letters, in which health and illness play such a prominent role, I occasionally noticed the topic in other literary texts as well, and I started asking myself if there were any patterns to the literary reflections of health and illness in early medieval literature. I was particularly interested in self-writings of all kinds, and in discovering ways of dealing with individual or familial health challenges in literary form.

If you had to distill it, what’s the central argument or theme readers should take away?

There are no long literary texts in early medieval China that are chiefly dedicated to the experience of being healthy or sick, and in most texts that we know health and illness hardly rise to the surface, although strong undercurrents of concern with physical matters can still be detected. What I would like to show my readers is that it can be enlightening to take note of the occasions when matters of health and illness do break through or when they are revealed in the workings of a text. To my mind, there is no master narrative or overarching philosophy of health and illness. Rather, there is a spectrum of narratives and philosophies depending on genre conventions and context.

How did you structure the research in this book? (Chronologically, by theme ect) Why did you decide to structure this way?

Since the pragmatic environment of illness narratives is so important, the book’s chapters are basically organized by genre: from essay to authorial preface, letter, scripture and poetry. At the same time this genre organization overlaps with a thematic organization: because literary genres require certain approaches—what to say and how to say it—the book’s structure is also determined by the questions that I asked of the texts.

What was the most challenging part of the research or writing process?

This would be selection and connection. Given the broad range and great number of early medieval Chinese literary texts that bring up health and illness in one way or another, I knew I had to be extremely selective in my presentation. Since I value the close analysis of literary texts, I decided to focus on case studies that allow exemplary glimpses into different parts of early medieval literature. Connecting these case studies with each other to form a more or less organic narrative was not only a challenge, but also a joyful process of connecting the dots and completing the puzzle, discovering the mycelial leads hidden in many texts and following them to other parts of the literary and cultural landscape.

Who do you imagine as the audience for this book?

I mainly envision three types of readers: those interested in everything to do with medieval Chinese literature and culture, those interested in illness narratives in literature more generally, which also includes readers interested in later periods of Chinese history, as well as historians of Chinese medicine.

What do you hope readers will be thinking about after finishing it?

I hope that readers will come away from the book with a strong sense of the lived reality in the Chinese Middle Ages. It’s easy to lose sight of the fact that the hallowed writers of old clearly understood themselves as living, thriving, aging, and often enough also suffering bodies. We share many of their concerns: how easy it is to overwork ourselves, how there are points in our lives and biographies where health and illness take center stage, how we are looking for a way to accept illness as part of the human condition. Trying to empathize across centuries is a good way to practice other types of empathy. Finally, I hope to inspire readers to dive into the literary texts themselves and to explore further.—There is so much more to discover.

Do you have any stories from the process—fieldwork, archival finds, or even how you chose the title/cover—that give readers a glimpse of how the book took shape?

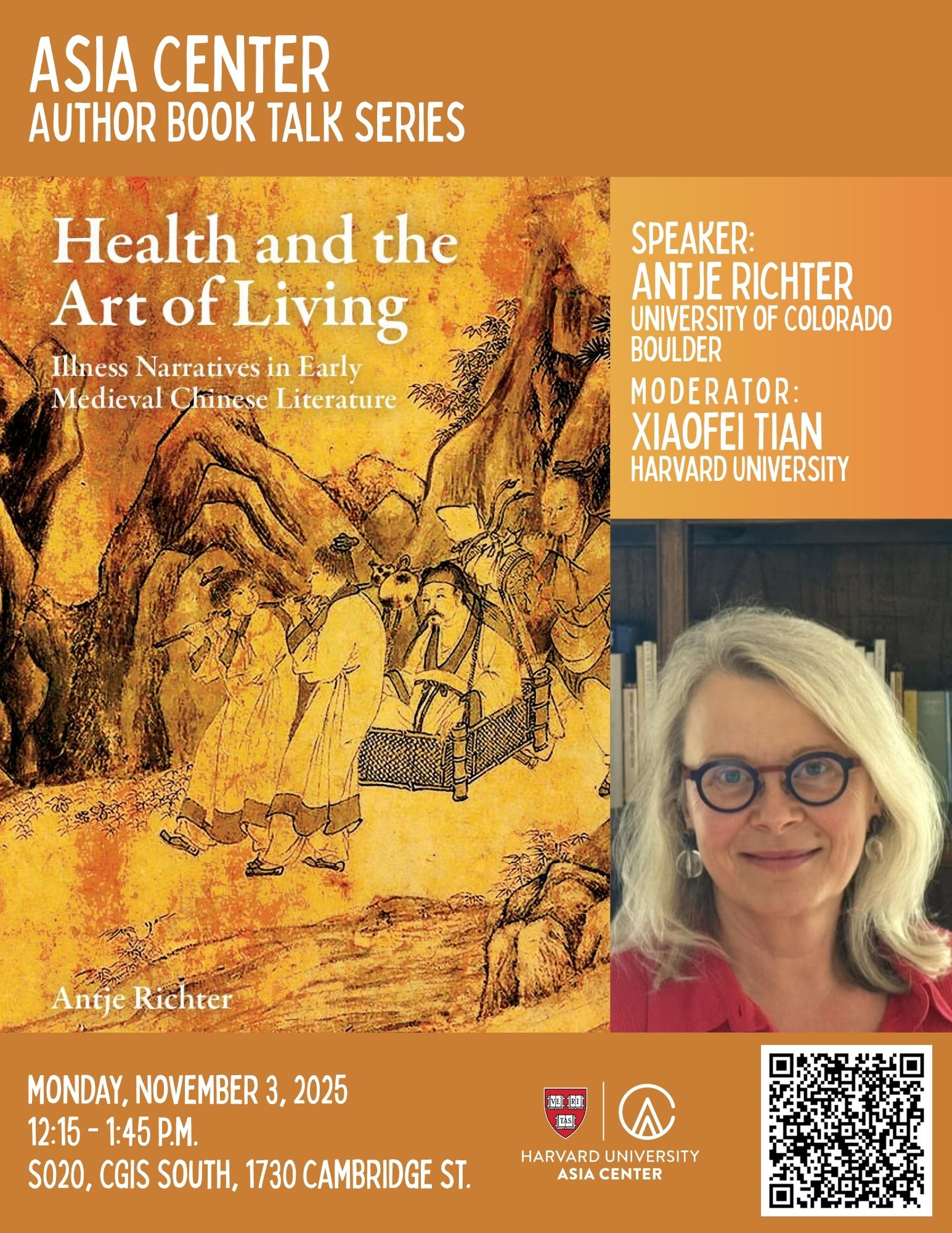

The cover of the book shows the poet Tao Qian being carried to Mount Lu in a basket because he was suffering from a foot illness and could not walk by himself. This detail of Tao Qian’s life is reported in early biographies and in later centuries became popular in painting as well. I was delighted when I found this particular handscroll of the “Lotus Society,” now stored in the National Museum of Asian Art in Washington, DC. Traditionally attributed to the Song dynasty painter Li Gonglin, but probably a sixteenth-century copy, the painting speaks to the long history and central place that illness claims in the Chinese cultural imaginaire.

** Antje Richter will be at Harvard on November 3rd, 2025 for a Book Talk about Health and the Art of Living: Illness Narratives in Early Medieval Chinese Literature**